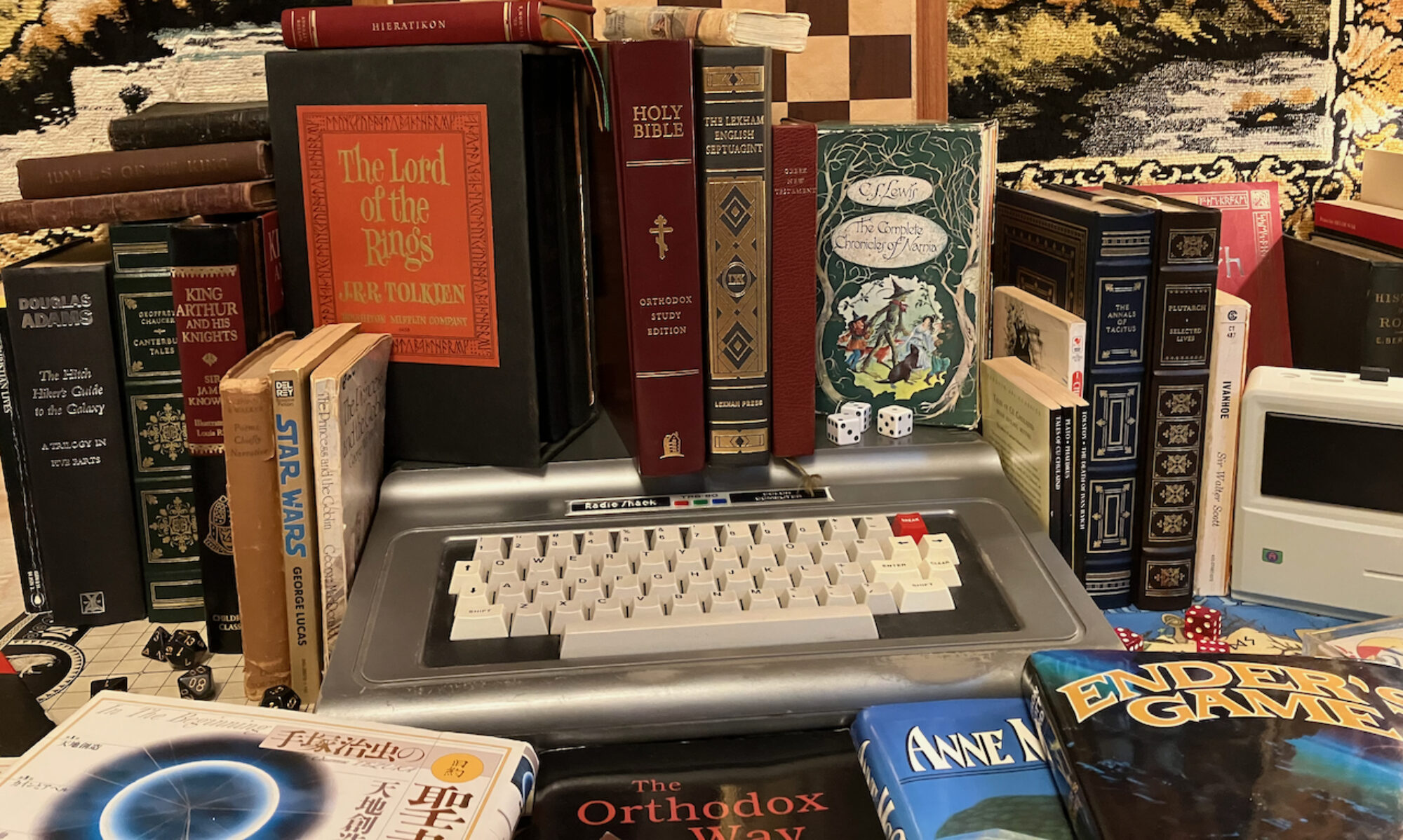

The keynote address I gave at Doxacon Seattle in 2019 on the trope of transformation in fantasy literature and its importance, alongside the importance of our embodiment, for our identity.

The geeks have inherited the earth.

Orthodox Christianity and geek subculture, hosted by Fr. Justin, an Orthodox priest and life-long book-, computer-, game-, sci-fi-, and fantasy-geek.

The keynote address I gave at Doxacon Seattle in 2019 on the trope of transformation in fantasy literature and its importance, alongside the importance of our embodiment, for our identity.

In which I read to you an essay I wrote long ago, in a faraway land called St. Vladimir’s Seminary.

Source:

The full text of the original essay can be found here, on ChristianFantasy.com

Related:

My favourite wedding homily, “Mawidge and True Love”, from my other podcast, Translating the Tradition

In which I reflect on some of the echoes of Arthurian legend in Lewis and Tolkien, and on some of the influence and significance of the death of Arthur for me

Show Notes:

Tolkien:

Lewis:

“When the Pevensie children had returned to Narnia last time for their second visit, it was (for the Narnians) as if King Arthur came back to Britain, as some people say he will. And I say the sooner the better.” –C.S. Lewis, The Voyage of the Dawn Treader

“The association of Arthur’s grave with Glasontbury can therefore be described briefly. The earliest written record is found in a work of the Welsh antiquary Giraldus Cambrensis, or Gerald of Wales, written near the end of the twelfth century. After observing that fantastical tales were told of Arthur’s body, as that it had been borne to a region far away by spirits and was not subject to death, he said that ‘in our days’ Arthur’s body had in fact been found, by the monks of the abbey of Glastonbury, buried deep in the ground in a hollowed oak in the graveyard. A leaden cross was fixed to the underside of a stone beneath the coffin, in such a way that an inscription on the cross was conceled. The inscription, which Giraldus himself had seen, declared that buried there was the renowned King Arthur together with Wennevaria in insula Avallonia [in the island Avallonia]. (He records also the curious detail that beside the bones of Arthur (which were of hugest size) and of Guinevere was a perfectly preserved tress of her golden hair, but that when it was touched by one of the monks it fell instantly to dust.) The date of this event is recorded as 1191.

In the same passage Giraldus said that what was now called Glastonia was anciently called Insula Avallonia. This name, he explained, arose because the place was virtually an island, entirely surrounded by marshes, whence it was called Britannice (in the British [i.e., Celtic] language) Inis Avallon, meaning, he said, insula pomifera ‘island of apples’, aval being the British word for ‘apple’, for apple-trees were once abundant there. He adds also that Morganis, who was a noble lady, akin to King Arthur, and ruler of that region, took him after the battle of Kemelen (Camlan) to the island which is now called Glastonia for the healing of his wounds.” –Christopher Tolkien, The Fall of Arthur

“‘Don’t you remember planting the orchard outside the north gate of Cair Paravel? The greatest of all the wood-people, Pomona herself, came to put good spells on it.’ …

‘[But] Cair Paravel wasn’t on an island.’

‘Yes, … but it was a what-do-you-call-it, a peninusla. Jolly nearly an island.

Couldn’t it have been made an island since our time? Somebody has dug a channel.'” –Peter and Edmund in Prince Caspian

Steinbeck:

“The western world and its so called culture have invented very few things,” he wrote in 1953. “But there is one thing that we invented and for which there is no counterpart in the east and that is gallantry. . . . It means that a person, all alone, will take on odds that by their very natures are insurmountable, will attack enemies which are unbeatable. And the crazy thing is that we win often enough to make it a workable thing. And also this same gallantry gives a dignity to the individual that nothing else ever has. . . .”

Shakespeare, Hamlet:

“Our indiscretion sometimes serves us well, when our deep plots do pall: and that should teach us there’s a divinity that shapes our ends, rough-hew them how we will…

Not a whit, we defy augury: there’s a special providence in the fall of a sparrow. If it be now, ’tis not to come, if it be not to come, it will be now; if it be not now, yet it will come: the readiness is all.” –Act V, Scene II

In which King Arthur and his death are presented in their most perfectly poetic and Christian form

Show Notes:

Date: AD 1859-1885

Isolt tells Tristam her response to the news he was married:

“‘I will flee hence and give myself to God’”, to which he jokingly replies:

Then Tristram, ever dallying with her hand,

“May God be with thee, sweet, when old and gray,

And past desire!” a saying that angered her.

“‘May God be with thee, sweet, when thou art old,

And sweet no more to me!’ I need Him now.

… lie to me: I believe.

Will ye not lie? not swear, as there ye kneel,

And solemnly as when ye sware to him,

The man of men, our King—My God, the power

Was once in vows when men believed the King!

They lied not then, who sware, and through their vows

The King prevailing made his realm:—I say,

Swear to me thou wilt love me even when old,

Gray-haired, and past desire, and in despair.””

Tristam: “Vows! did you keep the vow you made to Mark

More than I mine? Lied, say ye? Nay, but learnt,

The vow that binds too strictly snaps itself —

My knighthood taught me this — ay, being snapt —

We run more counter to the soul thereof

Than had we never sworn. I swear no more.

I swore to the great King, and am forsworn.

… The vows!

O, ay — the wholesome madness of an hour —

They served their use, their time; for every knight

Believed himself a greater than himself,

And every follower eyed him as a God;

Till he, being lifted up beyond himself,

Did mightier deeds than elsewise he had done,

And so the realm was made: but then their vows —

First mainly thro’ that sullying of our Queen —

Began to gall the knighthood, asking whence

Had Arthur right to bind them to himself?

… can Arthur make me pure

As any maiden child? lock up my tongue

From uttering freely what I freely hear?

Bind me to one? The wide world laughs at it.

And worldling of the world am I, and know

The ptarmigan that whitens ere his hour

Woos his own end; we are not angels here

Nor shall be: vows—I am woodman of the woods,

And hear the garnet-headed yaffingale

Mock them: my soul, we love but while we may;

And therefore is my love so large for thee,

Seeing it is not bounded save by love.”

Here ending, he moved toward her, and she said,

“Good: an I turned away my love for thee

To some one thrice as courteous as thyself—

For courtesy wins woman all as well

As valour may, but he that closes both

Is perfect, he is Lancelot—taller indeed,

Rosier and comelier, thou—but say I loved

This knightliest of all knights, and cast thee back

Thine own small saw, ‘We love but while we may,’

Well then, what answer?”

He that while she spake,

Mindful of what he brought to adorn her with,

The jewels, had let one finger lightly touch

The warm white apple of her throat, replied,

“Press this a little closer, sweet, until—

Come, I am hungered and half-angered—meat,

Wine, wine—and I will love thee to the death,

And out beyond into the dream to come.””

“Then in the light’s last glimmer Tristram showed

And swung the ruby carcanet. She cried,

“The collar of some Order, which our King

Hath newly founded, all for thee, my soul,

For thee, to yield thee grace beyond thy peers.”

“Not so, my Queen,” he said, “but the red fruit

Grown on a magic oak-tree in mid-heaven,

And won by Tristram as a tourney-prize,

And hither brought by Tristram for his last

Love-offering and peace-offering unto thee.”

He spoke, he turned, then, flinging round her neck,

Claspt it, and cried, “Thine Order, O my Queen!”

But, while he bowed to kiss the jewelled throat,

Out of the dark, just as the lips had touched,

Behind him rose a shadow and a shriek—

“Mark’s way,” said Mark, and clove him through the brain.

That night came Arthur home, and while he climbed,

All in a death-dumb autumn-dripping gloom,

The stairway to the hall, and looked and saw

The great Queen’s bower was dark,—about his feet

A voice clung sobbing till he questioned it,

“What art thou?” and the voice about his feet

Sent up an answer, sobbing, “I am thy fool,

And I shall never make thee smile again.””

Tennyson sort of follows Malory: Guinevere flees to a monastery when Mordred exposes her adultery with Lancelot (so, no rescue by Lancelot from burning, or return to Arthur, or fleeing from Mordred to the Tower and only after that to the convent – the idea of burning is there when Arthur confronts her and says that he considered burning her, according to the law, but he rejected that idea).

In Tennyson, Guinevere’s infidelity leads more directly to the downfall of the Round Table and the kingdom.

Arthur to Guinevere:

“Howbeit I know, if ancient prophecies

Have erred not, that I march to meet my doom.

Thou hast not made my life so sweet to me,

That I the King should greatly care to live;

For thou hast spoilt the purpose of my life.

Bear with me for the last time while I show,

Even for thy sake, the sin which thou hast sinned.

For when the Roman left us, and their law

Relaxed its hold upon us, and the ways

Were filled with rapine, here and there a deed

Of prowess done redressed a random wrong.

But I was first of all the kings who drew

The knighthood-errant of this realm and all

The realms together under me, their Head,

In that fair Order of my Table Round,

A glorious company, the flower of men,

To serve as model for the mighty world,

And be the fair beginning of a time.

I made them lay their hands in mine and swear

To reverence the King, as if he were

Their conscience, and their conscience as their King,

To break the heathen and uphold the Christ,

To ride abroad redressing human wrongs,

To speak no slander, no, nor listen to it,

To honour his own word as if his God’s,

To lead sweet lives in purest chastity,

To love one maiden only, cleave to her,

And worship her by years of noble deeds,

Until they won her; for indeed I knew

Of no more subtle master under heaven

Than is the maiden passion for a maid,

Not only to keep down the base in man,

But teach high thought, and amiable words

And courtliness, and the desire of fame,

And love of truth, and all that makes a man.

And all this throve before I wedded thee,

Believing, ‘lo mine helpmate, one to feel

My purpose and rejoicing in my joy.’

Then came thy shameful sin with Lancelot;

Then came the sin of Tristram and Isolt;

Then others, following these my mightiest knights,

And drawing foul ensample from fair names,

Sinned also, till the loathsome opposite

Of all my heart had destined did obtain,

And all through thee! ..

…

…how to take last leave of all I loved?

…

My love through flesh hath wrought into my life

So far, that my doom is, I love thee still.

Let no man dream but that I love thee still.

Perchance, and so thou purify thy soul,

And so thou lean on our fair father Christ,

Hereafter in that world where all are pure

We two may meet before high God, and thou

Wilt spring to me, and claim me thine, and know

I am thine husband—not a smaller soul,

Nor Lancelot, nor another. Leave me that,

I charge thee, my last hope.”

“And while she grovelled at his feet,

She felt the King’s breath wander o’er her neck,

And in the darkness o’er her fallen head,

Perceived the waving of his hands that blest.”

Guinevere’s response:

“shall I kill myself?

What help in that? I cannot kill my sin,

If soul be soul; nor can I kill my shame;

No, nor by living can I live it down.

…

I must not dwell on that defeat of fame.

Let the world be; that is but of the world.

What else? what hope? I think there was a hope,

Except he mocked me when he spake of hope;

His hope he called it; but he never mocks,

For mockery is the fume of little hearts.

And blessed be the King, who hath forgiven

My wickedness to him, and left me hope

That in mine own heart I can live down sin

And be his mate hereafter in the heavens

Before high God. Ah great and gentle lord,

Who wast, as is the conscience of a saint

Among his warring senses, to thy knights—

To whom my false voluptuous pride, that took

Full easily all impressions from below,

Would not look up, or half-despised the height

To which I would not or I could not climb—

I thought I could not breathe in that fine air

That pure severity of perfect light—

I yearned for warmth and colour which I found

In Lancelot—now I see thee what thou art,

Thou art the highest and most human too,

Not Lancelot, nor another. …

…

What might I not have made of thy fair world,

Had I but loved thy highest creature here?

It was my duty to have loved the highest:

It surely was my profit had I known:

It would have been my pleasure had I seen.

We needs must love the highest when we see it,

Not Lancelot, nor another.”

“For on their march to westward, Bedivere,

Who slowly paced among the slumbering host,

Heard in his tent the moanings of the King:

“I found Him in the shining of the stars,

I marked Him in the flowering of His fields,

But in His ways with men I find Him not.

I waged His wars, and now I pass and die.

O me! for why is all around us here

As if some lesser god had made the world,

But had not force to shape it as he would,

Till the High God behold it from beyond,

And enter it, and make it beautiful?

Or else as if the world were wholly fair,

But that these eyes of men are dense and dim,

And have not power to see it as it is:

Perchance, because we see not to the close;—

For I, being simple, thought to work His will,

And have but stricken with the sword in vain;

And all whereon I leaned in wife and friend

Is traitor to my peace, and all my realm

Reels back into the beast, and is no more.

My God, thou hast forgotten me in my death;

Nay—God my Christ—I pass but shall not die.””

“Then spake the King: “My house hath been my doom.

But call not thou this traitor of my house

Who hath but dwelt beneath one roof with me.

My house are rather they who sware my vows,

Yea, even while they brake them, owned me King.

And well for thee, saying in my dark hour,

When all the purport of my throne hath failed,

That quick or dead thou holdest me for King.

King am I, whatsoever be their cry;

And one last act of kinghood shalt thou see

Yet, ere I pass.” And uttering this the King

Made at the man: then Modred smote his liege

Hard on that helm which many a heathen sword

Had beaten thin; while Arthur at one blow,

Striking the last stroke with Excalibur,

Slew him, and all but slain himself, he fell.”

“Then went Sir Bedivere the second time

Across the ridge, and paced beside the mere,

Counting the dewy pebbles, fixed in thought;

But when he saw the wonder of the hilt,

How curiously and strangely chased, he smote

His palms together, and he cried aloud:

“And if indeed I cast the brand away,

Surely a precious thing, one worthy note,

Should thus be lost for ever from the earth,

Which might have pleased the eyes of many men.

What good should follow this, if this were done?

What harm, undone? Deep harm to disobey,

Seeing obedience is the bond of rule.

Were it well to obey then, if a king demand

An act unprofitable, against himself?

The King is sick, and knows not what he does.

What record, or what relic of my lord

Should be to aftertime, but empty breath

And rumours of a doubt? But were this kept,

Stored in some treasure-house of mighty kings,

Some one might show it at a joust of arms,

Saying, ‘King Arthur’s sword, Excalibur,

Wrought by the lonely maiden of the Lake.

Nine years she wrought it, sitting in the deeps

Upon the hidden bases of the hills.’

So might some old man speak in the aftertime

To all the people, winning reverence.

But now much honour and much fame were lost.”

So spake he, clouded with his own conceit,

And hid Excalibur the second time,

And so strode back slow to the wounded King.

Then spoke King Arthur, breathing heavily:

“What is it thou hast seen? or what hast heard?”

And answer made the bold Sir Bedivere:

“I heard the water lapping on the crag,

And the long ripple washing in the reeds.”

To whom replied King Arthur, much in wrath:

“Ah, miserable and unkind, untrue,

Unknightly, traitor-hearted! Woe is me!

Authority forgets a dying king,

Laid widowed of the power in his eye

That bowed the will. I see thee what thou art,

For thou, the latest-left of all my knights,

In whom should meet the offices of all,

Thou wouldst betray me for the precious hilt;

Either from lust of gold, or like a girl

Valuing the giddy pleasure of the eyes.

Yet, for a man may fail in duty twice,

And the third time may prosper, get thee hence:

But, if thou spare to fling Excalibur,

I will arise and slay thee with my hands.””

“Then loudly cried the bold Sir Bedivere:

“Ah! my Lord Arthur, whither shall I go?

Where shall I hide my forehead and my eyes?

For now I see the true old times are dead,

When every morning brought a noble chance,

And every chance brought out a noble knight.

Such times have been not since the light that led

The holy Elders with the gift of myrrh.

But now the whole Round Table is dissolved

Which was an image of the mighty world,

And I, the last, go forth companionless,

And the days darken round me, and the years,

Among new men, strange faces, other minds.”

And slowly answered Arthur from the barge:

“The old order changeth, yielding place to new,

And God fulfils himself in many ways,

Lest one good custom should corrupt the world.

Comfort thyself: what comfort is in me?

I have lived my life, and that which I have done

May He within himself make pure! but thou,

If thou shouldst never see my face again,

Pray for my soul. More things are wrought by prayer

Than this world dreams of. Wherefore, let thy voice

Rise like a fountain for me night and day.

For what are men better than sheep or goats

That nourish a blind life within the brain,

If, knowing God, they lift not hands of prayer

Both for themselves and those who call them friend?

For so the whole round earth is every way

Bound by gold chains about the feet of God.

But now farewell. I am going a long way

With these thou seest—if indeed I go

(For all my mind is clouded with a doubt)—

To the island-valley of Avilion;

Where falls not hail, or rain, or any snow,

Nor ever wind blows loudly; but it lies

Deep-meadowed, happy, fair with orchard lawns

And bowery hollows crowned with summer sea,

Where I will heal me of my grievous wound.”

So said he, and the barge with oar and sail

Moved from the brink, like some full-breasted swan

That, fluting a wild carol ere her death,

Ruffles her pure cold plume, and takes the flood

With swarthy webs. Long stood Sir Bedivere

Revolving many memories, till the hull

Looked one black dot against the verge of dawn,

And on the mere the wailing died away.

But when that moan had past for evermore,

The stillness of the dead world’s winter dawn

Amazed him, and he groaned, “The King is gone.”

And therewithal came on him the weird rhyme,

“From the great deep to the great deep he goes.”

Whereat he slowly turned and slowly clomb

The last hard footstep of that iron crag;

Thence marked the black hull moving yet, and cried,

“He passes to be King among the dead,

And after healing of his grievous wound

He comes again; but—if he come no more—

O me, be yon dark Queens in yon black boat,

Who shrieked and wailed, the three whereat we gazed

On that high day, when, clothed with living light,

They stood before his throne in silence, friends

Of Arthur, who should help him at his need?”

Then from the dawn it seemed there came, but faint

As from beyond the limit of the world,

Like the last echo born of a great cry,

Sounds, as if some fair city were one voice

Around a king returning from his wars.

Thereat once more he moved about, and clomb

Even to the highest he could climb, and saw,

Straining his eyes beneath an arch of hand,

Or thought he saw, the speck that bare the King,

Down that long water opening on the deep

Somewhere far off, pass on and on, and go

From less to less and vanish into light.

And the new sun rose bringing the new year.”

In which we dive into the definitive English rendition of the legend of King Arthur to examine Sir Thomas Malory’s complex and nuanced handling of the causes and implications of King Arthur’s death

Show Notes:

In which we examine the transition from the treatment of Arthur as a primarily historical to a primarily literary figure in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s History of the Kings of Britain, and the resultant changes to the handling and implications of Arthur’s death

Show Notes:

1. Geoffrey of Monmouth, History of the Kings of Britain

Geoffrey’s influential History established Arthurian legend as the English ur-text, the “matter of Britain” and inspired a whole range of imaginative elaborations, most notably the addition of Lancelot by the French, writing in the “courtly love” tradition which Lewis engages with in his most important academic work, The Allegory of Love, as well as English works such as the alliterative Morte Arthure, which seems to have inspired the beginnings of Malory’s great Arthurian work.

In which we begin our in-depth engagement with “The Deaths of Arthur” by examining the historical context and sources for Arthur and the significance of his death.

Show Notes:

Notes:

In which I outline my intentions for the podcast.

Show Notes:

The Doxacon Seattle talk that started it all…