In which we examine the transition from the treatment of Arthur as a primarily historical to a primarily literary figure in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s History of the Kings of Britain, and the resultant changes to the handling and implications of Arthur’s death

Show Notes:

1. Geoffrey of Monmouth, History of the Kings of Britain

- Date: AD 1138

- Causes of Arthur’s death:

- Mordred’s betrayal: Arthur’s nephew, who is left in charge during Arthur’s Roman campaign, rebels and marries Guinevere

- Civil war: Arthur dies fighting his fellow Britons and a collection of enemies, primarily Saxons, but also “Scots, Picts, Irish” and others

- Aftermath:

- Guinevere (Guanhumara) flees to a convent

- Arthur “mortally wounded” and carried to the isle of Avallon to be cured

- kinsman Constantine succeeds the throne, but a rapid succession of rivals replacing one another as well as civil war over the next ten years or so leads to the wasting of what is left to them and the domination of the Saxons

- Beginnings of the subsequent shape of the “matter of Britain”:

- Theme of freedom: Uther, on defeating the Saxons (leading his troops on a litter due to illness): “Victory to me half-dead is better than to be safe and sound and vanquished. For to die with honour is preferable to living with disgrace.”

- Mordred’s betrayal, left in charge because he is Arthur’s kinsman (though here nephew, not son)

- Guinevere’s infidelity (though with Mordred)

- Single-combat between Arthur and Flollo looks a lot like a joust

- Tournaments: three-day tournament at the coronation, with prizes given on the fourth, including: “The military men composed a kind of diversion in imitation of a fight on horseback; and the ladies, placed in a sportive manner darted their amorous glances at the courtiers, the more to encourage them.”

- Civil war, which Geoffrey condemns: “Why foolish nation! oppressed with the weight of your abominable wickedness, why did you, in your insatiable thirst after civil wars, so weaken yourself by domestic confusions, that whereas formerly you brought distant kingdoms under your yoke, now, like a good vineyard degenerated and turned to bitterness, you cannot defend your country, your wives, and children, against your enemies?”

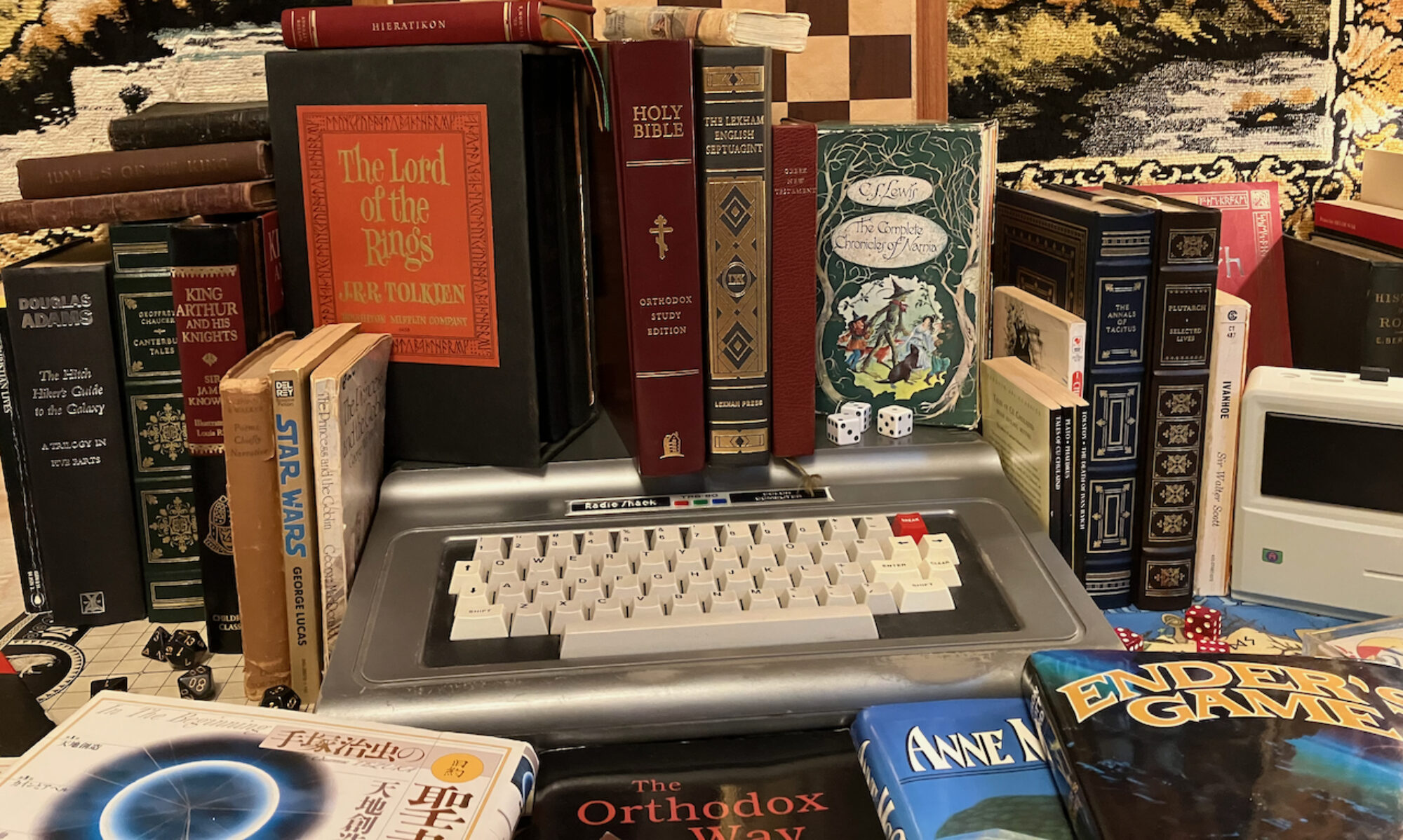

- Geoffrey’s account, written in Latin and thus widely disseminated, was hugely popular and influential, but was not well received by all his contemporaries – or even by later critics, like C.S. Lewis.

- William of Newburgh (c. 1196) condemns Geoffrey for weaving “ridiculous figments of imagination” around historical events recorded by the Venerable Bede and cloaked these old, British “fables about Arthur … with the honorable name of history by presenting them with the ornaments of the Latin tongue.” It is interesting that one of the possible motives he ascribes to Geoffrey for doing so is “to please the Britons, most of whom are known to be so primitive that they are said still to be awaiting the return of Arthur, and will not suffer themselves to hear that he is dead.” William wonders how “the old historians, to whom it was a matter of great concern that nothing worthy of memory should be omitted from what was written … could … have suppressed with silence Arthur and his acts, this king of the Britons who was nobler than Alexander the Great,” and further disparages Geoffrey for translating “the fallacious prophecies of a certain Merlin, to which he has in any event added many things himself” into Latin.

- Gerald of Wales, who writes an account of the discovery of King Arthur’s body (more on that later), condemns Geoffrey’s History with the story of a man who could see demons: “When he was harrassed beyond endurance by these unclean spirits, Saint John’s Gospel was placed on his lap, and then they all vanished immediately, flying away like so many birds. If the Gospel were afterwards removed and the History of the Kings of Britain by Geoffrey of Monmouth put there in its place, just to see what would happen, the demons would alight all over his body, and on the book too, staying there longer than usual and being even more demanding.”

- Lewis, on the other hand, condemns Geoffrey from a more modern, literary perspective: “Geoffrey is of course important for the historians of the Arthurian Legend; but since the interest of those historians has seldom lain chiefly in literature, they have not always remembered to tell us that he is an author of mediocre talent and no taste. In the Arthurian parts of his work the lion’s share falls to the insufferable rigamarole of Merlin’s prophecies and to the foreign conquests of Arthur. These latter are, of course, at once the least historical and the least mythical thing about Arthur. If there was a real Arthur he did not conquer Rome. … The annals of senseless and monotonously successful aggression are dreary enough reading even when true; when blatantly, stupidly false, they are unendurable.”

2. Intermediate sources I’m going to skip

Geoffrey’s influential History established Arthurian legend as the English ur-text, the “matter of Britain” and inspired a whole range of imaginative elaborations, most notably the addition of Lancelot by the French, writing in the “courtly love” tradition which Lewis engages with in his most important academic work, The Allegory of Love, as well as English works such as the alliterative Morte Arthure, which seems to have inspired the beginnings of Malory’s great Arthurian work.

- French prose cycle: Lancelot, Quest for the Grail, Mort Artu (Malory’s “French book”)

- 14th C English alliterative Morte Arthure

- 14th C stanzaic Le Morte Arthur